As we look ahead to the planting season, land preparation is already underway. We run through some pointers on what to look for when preparing fields, to make sure that you give your crops the best chance this year.

Number one for me is always dig a hole. This allows you to not only examine the soil structure and see where there are any hard pans created by previous cultivations or field operations such as harvesting in the wet, but the effort of doing the physical digging gives you a lot of information on the soil structure.

Look for roots right through the profile, like the sorghum crop on the left. A healthy soil should have an open, porous soil structure with plenty of space for air and water – worm holes are a good sign on the right.

Dig a number of holes across different soil types and fields and vary the depth; one or two deep holes at least one metre are always useful to see exactly where last year’s roots were going, and what might have been stopping or impeding them.

Hard, dense layers caused by compaction are often very shallow in the North Rift, resulting from years of disc ploughing at the same depth. In some soils in the Southern Rift I often see deeper layers caused by harvesting machinery in the Short Rains. In Narok, it is unusual to find soil that is NOT compacted by cattle grazing.

Several years ago I remember finding a hard layer on a farm in Naivasha that was 40-45cm deep across the farm. It was only because we dug by hand that I could feel the soil becoming hard at this depth – a pass with a subsoiler and a crop of canola transformed the fields.

Looking at the roots will tell you a lot – do you find horizontal growth and parts of the soil where the clods are suddenly devoid of roots? If compaction is not the obvious cause, examine the colour and fineness of the roots – diseases or nematodes could easily be stopping the crop from rooting deeper and accessing moisture later in the season.

This field grew potatoes our years ago and was left in very poor structure because of the wet harvest at the time. Now planted to canola, the plant on the left was from a tramline that had been subsoiled, the plant on the right is from a compacted area and has no taproot.

I also advocate taking soils at depth through the profile – occasionally you will find a more acidic layer at depth or a very inert layer that appears to have no nutrients and the crop just does not want to grow through it.

With a bit of help from a crop like sorghum or sunflowers, this can change over time and unlock a lot of hidden moisture and nutrients below it. You should be soil testing every field regularly as advised. Fertiliser is expensive enough, but the real cost of poor fertiliser decisions is in the yield lost.

As a general rule, if you do find a compacted or hard layer, you need to use a tine cultivator like a chisel plough or subsoiler. Aim to set it 5-10 cm below the layer of compaction and dig holes behind it to check that it is breaking the layer effectively – the soil needs to be reasonably dry for a full shattering effect, so aim to do this in January or February. This is also a great opportunity to incorporate lime into the profile too.

Finally, remember to set tyre pressures on machinery correctly. The manufacturer’s handbook will give you the pressures so that you avoid further compaction and optimise fuel economy.

There are some excellent locally-made chisel ploughs like this one on the tractor. Seldom have I seen soil in Trans Nzoia where a chisel has not given at least a 5 bag per acre yield boost compared to a disc plough.

The most important day in a crop’s life is the day it is planted. This is a fundamental that has not changed over the years and is every bit relevant to a ½ acre smallholder as it is to a 1,000-acre farmer.

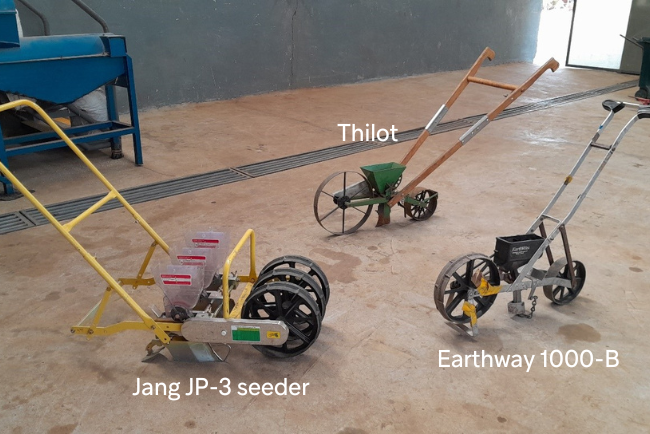

But how do you go about ensuring consistent, even depth of seed placement if you do not have access to mechanized equipment? Within our trials team, we have faced this challenge for years and have been using the following push-along tools to speed up planting and increase accuracy.

Firstly, we are assuming that the soil has been cultivated and is reasonably level and flat. No planting – by machine or by hand – can make up for poor land preparation.

We have used these single-row, push-along seeders for several years and they are among our favourites. Lightweight, very strong, simple, and easy to calibrate by changing seed discs (the machine comes with a set of six different-sized discs for various crops – you can also block holes with tape in order to create your own see rate and spacing.

The Earthway works well in wet or dry soil, and copes with residue although the chain can drag debris and block occasionally. Large seeds can also block the seed chute which is also a pain, because it relies on the operator being attentive and watching the seeds fall.

Large seeds with rough coats like chickpeas do not flow well through the planter either and for the very smallest seed such as canola, it cannot cope. Thankfully it can meter out fertiliser successfully – in a separate pass before seeding – which is very useful.

The Jang JP-3 is a three-row, precision metering planter that relies on well-cultivated, fine soil. It is a relatively heavy planter and it does take some experience to push it straight and achieve accurate rows, but being three rows it is very fast and accurate. The beauty of this machine is that rows can be removed or added, so you can reduce the effort required in crops that do not mind wider rows.

We find that this planter can block occasionally, and it takes a lot of trial and error to set it up and get the calibration right for different crops and seeds. The calibration is set by changing a series of sprockets on a chain to alter the speed, so it is the more complex of the three machines we use.

But because you can see the seed going through the metering rolls, it gives you a lot of confidence that the machine is working accurately. The Jang seeder is great for vegetables and we even use it for cereals and small peas, and once you have worked out the setting and recorded them, this is a very fast and efficient machine.

A much heavier-duty single-row planter, that we favour in dry, cloddy conditions and for very small and very large seeds. This is not a precision seeder, so the spacing between seeds will not be at all uniform.

The seeder uses a brush in the hopper to agitate the seed through a hole. The operator changes the size of the hole by rotating a disc on the back of the hopper.

The seeder is very effective for small seeded canola and large pulses such as dry beans, peas, and broad beans / faba beans, but its one weakness is it does not always cover the seed fully. Whilst very robust this is a heavy seeder that requires a lot of effort to push.

| Earthway 1000-B | Thilot | Jang JP-3 | |

| Weight | Light | Very heavy | Heavy |

| Effort required to push | Low | High | High (plants 3 rows) |

| Performance in wet | Poor | OK | Very poor |

| Depth accuracy | Good | Very good | Good |

| Covering the seed | Good | OK | Very good |

| Strength of design | Strong | Strong | Fair |

| Complexity | Fair | Simple | Very complex |

| Speed of planting | Fast | Moderate | Very fast |

| Adjustability of seed rate | OK – change between discs | OK – change between hole sizes at the outlet | Good but slow – involves removing gears |

| Blockages | Common | Uncommon | Common |

And what about hand planting? Depth of placement is never as good as with a mechanical planter. To plant a small trial plot of maize, it takes me around 15 seconds per square meter to individually push each seed into the correct depth, and that assumes the starter fertiliser is already put down. For wheat, barley, peas and many vegetable crops I can always get a better results with one of the above machines.

Most farmers have always planted cereals with chemical seed dressings. But what do the seed dressings really do, and what are the implications of planting untreated seed? Whilst there is a potential cost and time saving from not dressing seed, it is important to be aware of the risks and additional costs further down the line.

Centuries ago, it was not uncommon for entire local areas or villages to experience crop failure with seed-borne diseases such as Bunt. Before proper seed certification systems had been developed, it was very common for popular ‘landraces’ to be sold and passed locally between farmers. Without seed-borne disease testing this was a very effective way of spreading problems to unwitting farmers.

In the case of Bunt and Smut, crops would look good all season until a few weeks before harvest, when the disease would appear and cause total crop loss. Seed treatment chemicals have developed over the years to address these problems and as a result, have largely eliminated issues with entire fields of Bunt and Loose Smut.

Generally, any seed dressing containing prothioconazole, fludioxonil, difenconazole, ipconazole or triticonazole will control Bunt, Loose Smut and seedling death caused by Fusarium and Michrodochium. This is standard, basic level of protection.

In cooler conditions and slow crops, occasionally Septoria seedling blight will reduce establishment, and Fludioxonil has useful activity on this. In Kenya this is less of an issue.

There are more specialist seed dressings that can help with specific diseases such as Take-all (silthiofam or fluqinconazole + prochloraz) or Rhizoctonia (sedexane). A very interesting product in development is cyclobutrifluram which helps control nematodes and Crown Rot. This could be very interesting in drier regions. These specialist dressings tend to add a lot of cost and are only worthwhile if a specific problems needs addressing.

Most seed treatments also contain insecticide dressings, typically with a neonicotinoid such as imidacloprid, thiamethoxam or clothianidin. These all give very good control of aphids for around 8 weeks – usually enough to prevent aphids infecting the crop with Barley Yellow Dwarf virus and to keep Russian Wheat Aphid out.

I have learnt the hard way over the years that if I do not apply an insecticide on the seed, over 70% of the time I have to come back with a foliar insecticide spray for aphids which is less targeted…. And the damage has already lost some yield.

Cutworm is rarely controlled well by seed dressings, although clothianidin is probably the better of the available options. This also has useful slug activity where these are a problem at establishment, but is probably slightly less persistent on Russian Wheat Aphids than thiamethoxam.

Seed treatments can also help control foliar diseases. Adding a few grams of fluopyram or fluxapyroxad is common for reducing early Net Blotch in barley, which is often seed borne as well as spread into the crop from surrounding barley stubbles. Fluquinconazole and triadimenol provide several weeks of Yellow Rust protection, but even in very Yellow Rust susceptible varieties it does not alter the need to apply a T1 spray at growth stage 30 so will unlikely save money.

A final important point that is often misunderstood is that the devastating effects of Bunt and Smut have been suppressed by collective industry action. If you stop using seed dressings, it is unlikely (but possible) that you will have an immediate catastrophic crop failure. But if everyone were to stop using them, that is when problems are likely to occur (dare I draw comparisons with Covid vaccinations?!). The simplest answer is to dress for the diseases you need to protect against, and to ALWAYS get a lab test done before you plant untreated seed.

Till next time,

David Jones,

Independent Agronomist

How would you rate our article?

David is an independent agronomist in Kenya and a member of the Association of Independent Crop Consultants. David gives independent advice based on scientific trials and experience. Currently works with the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation.

Think Agronomy is brought to you by Cropnuts and the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation. We share the same vision for sustainable, dryland farming across Africa, and Think Agronomy is our independent voice to promote profitable, climate-resilient farming through better management of soil health, systems-based agronomy, crop diversification, and farm mechanization.

Order our services and get to know how to improve your soil for better yeilds.