A good crop begins with putting the seed in the ground well, into a good growing environment. This means a well-structured soil with plenty of oxygen so that the roots can explore and grow rapidly in length and access as much soil volume as possible. In turn, this allows the growing crop to access more nutrients, more water and anchor itself strongly.

This soil preparation means many things to many farmers, and there is never a single approach for everyone; it depends on soil type, the crop to be grown, the existing soil structure and indeed the equipment available.

Traditionally, in Kenya, disc ploughing has taken place from November through to February to cultivate the land ready for planting, but is this the best technique and what implications does it have for the growing crop?

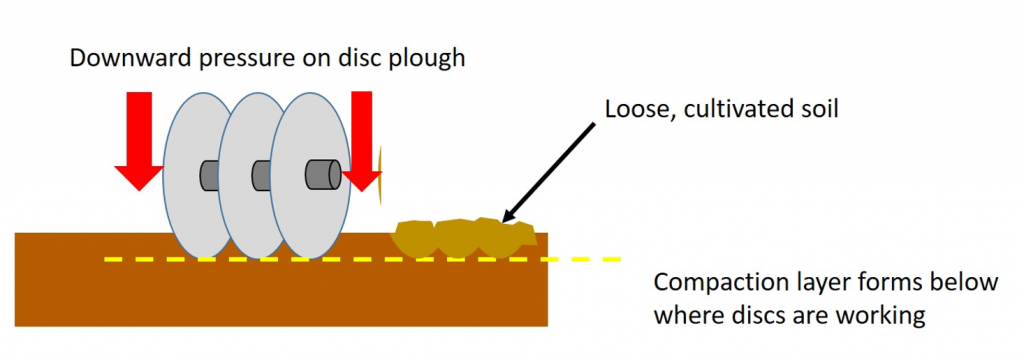

One of the issues with disc ploughs is that they create a very hard pan of soil at the depth below the bottom of the disc each year, making it hard – sometimes impossible – for the crop to put its roots through. Because the disc plough works very shallow this severely restricts the volume of soil available, leading the crop to suffer very quickly in a dry period.

It is also very common for the disc plough to leave the surface rough and uneven. This is very bad news for maize in particular, where all of the plants need to emerge on the same day to avoid yield loss from the earlier plants shading the later plants – which are in fact weeds as they contribute far less to yield but still take a disproportionate amount of light and nutrients.

One technique gaining popularity is the chisel plough. This is an implement which uses a series of deeper legs or ‘tines’ to rip the soil. Because this works at a greater depth than a disc plough and is not ‘weighing’ on the soil and smearing a layer at the bottom of a disc, it is very effective at removing compaction and providing an open soil structure.

More importantly, it allows water to infiltrate much quicker, meaning that small amounts of rain go a lot further into the soil to be stored for when the crop needs it.

Chisel ploughs take more power to pull, but vastly improve yields compared to a disc plough. They do leave the soil surface uneven, so a pass with a harrow afterwards is a very good way to prepare the soil for sowing.

Gaining popularity amongst medium and larger scale farmers is a disc and tine combination cultivator. Often referred to as a ‘one-pass’ cultivator this is a misnomer; cultivation and land preparation should take as many passes as needed to create a good seedbed. Sometimes one pass will be sufficient, other times three separate passes may be needed to achieve the desired seedbed.

These cultivators to a great job of deep loosening with the tines, as well as mixing and chopping the clods and trash to give a well-structured, level seedbed. Occasionally they can do too much soil disturbance and they do take a lot of power to pull.

Among some large farms, notill or direct drilling is gaining popularity. Whilst this is a very low-cost method of establishing a crop, as only a single pass with the planter is required, there is a lot of longer-term discipline and preparation to make this work – something we will discuss later this year.

Sclerotinia can be a serious cause of yield loss in canola, as infected petals drop onto the stems at flowering and cause the upper branches to die before the seeds have filled. In worst cases, the entire plant is killed and in bad years 50% yield loss is not unheard of. Thankfully, this is a disease that can be managed by a combination of cultural, non-chemical practices – and fungicides.

As well as chemistry, cultural controls are very effective at reducing Sclerotinia and the need for fungicides. Long rotations between brassica crops cause a decline in the sclerotia (the fruiting bodies of the pathogen that survive in the soil) over time, so think carefully about field history when deciding on crop rotation.

Remember that cabbage, broccoli, lettuce, and sunflowers are all major hosts of Sclerotinia so they do not count as a break! Try to keep at least 4 years between any of these crops or canola.

Peas, chickpeas, and potatoes are also hosts of Sclerotinia if you read the textbooks, but from experience, they contribute minimally to the disease build up and are rarely affected themselves by Sclerotinia.

We are not that far from Sclerotinia tolerant varieties appearing on farms, although this ‘resistance’ is only partial. Already appearing on farms in Canada, France, and UK, these varieties have a level of resistance to the disease. Having trialled such varieties in several high Sclerotinia pressure farms in Kenya, we are definitely not there yet.

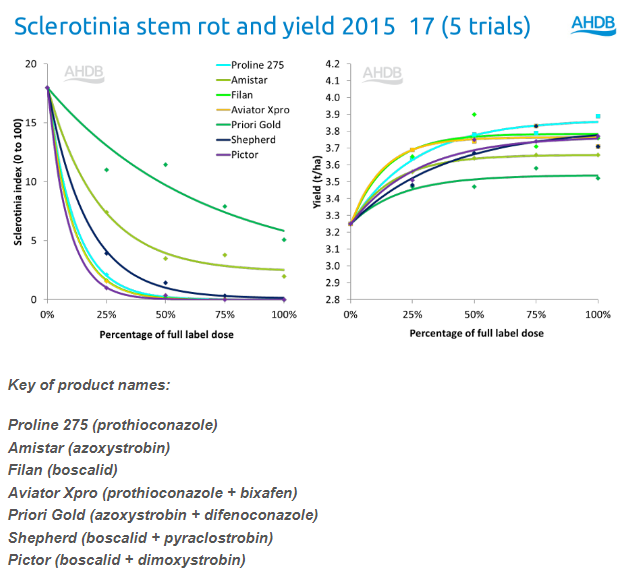

So where do you look for actual data on what fungicides to use? Thankfully, as the Sclerotinia pathogen is virtually identical across the world, we can look at work from many other countries to compare the options and their effectiveness.

For years azoxystrobin has been, and still is, highly effective and is available in several products. Shortly after azoxystrobin became available, prothioconazole was released and found to be highly effective. Most data now suggests that it has the edge over azoxystrobin and it is also very good at Blackleg or Stem Canker (which presents a dilemma, as we don’t want to over-use prothioconazole which could lead to resistance developing).

Boscalid is a more recent active ingredient that is very strong against Sclerotinia, often sold in co-forms with pyraclostrobin. Most data would suggest that this provides the highest level of control (with a cost attached!) which follows through to yield.

It is worth noting that tebuconazole is not particularly effective against Sclerotinia, so whilst it is inexpensive and widely available it is best avoided.

The charts below from independent trials in the UK show the effect of each product against Sclerotinia on the left. The line represents the effect of increasing the fungicide dose on the % of disease, so the steeper and lower the line the better control of Sclerotinia is achieved. On the right is the final yield, showing how the yield increases as the fungicide dose increases and improves disease control.

Perhaps the most important point is to apply a good product, at the 30% flowering before the first petal fall, and to rotate chemistry to not become overly reliant on a single group or mode of action.

In some years, high rainfall and thick, dense crops will justify a 2nd spray at flowering. To put it into context, if a typical fungicide costs 3,000 Ksh/ha it only needs to save 40kg of yield to cover its cost and start making you money.

Lastly, beware of claims of greening effects; there is a supposition that this effect (which is by no means reliable) guarantees more yield but it is certainly not necessarily the case. To the point that in many countries where reliable, independent trial data is generated you will never hear this talked about. Yield alone is what pays the bills, not visual appearance!

Good weed control is crucial in peas to protect yield, ensure a clean sample at harvest, and to provide options to make the following crop a success. Importantly, this involves treating the crop delicately to avoid causing injury with herbicides – a frequent occurrence in peas!

The most important point is to start pre-emergence and to understand the likely weeds on the particular shamba. Once you know what weeds are likely to be a problem you can then match the products to control them.

Metribuzin (available as Sencor and others) is very effective and forms the cornerstone for many herbicide programs, providing good control of Amaranthus, Wild Radish, and Gallant Soldier. It is also relatively cheap. Must be applied pre-emergence.

Linuron, available as various products is expensive but improves Nightshade / Wild Tomato control, and helps with Bindweed control – a very problematic weed if you are harvesting peas with a combine. Normally you know if these weeds are likely to be a problem, so add it only if necessary (See The Arable Weed Control Guide).

Pendimethalin can also be used successfully in peas but it tends to break down too quickly to be relied upon. Pendimethalin mixed with Sencor covers most weeds and is very effective.

Clomazone is great and is an absolute must for Cleavers in higher altitude areas – this weed can make harvest very difficult as it wraps around the combine reel. Clomazone also adds to chenopodium control (Fat Hen or Lamb’s Quarter) but it must be applied carefully due to its volatility.

Acetochlor and S-metolachlor are both very useful products that provide good control of a range of broadleaved weeds.

For post-emergence control, bentazone is really the only option, and it hits the crop hard, especially in bright conditions. Check leaf wax before you spray peas with bentazone, by rubbing your finger on the leaf; if it turns from a dull waxy colour to a shiny green then it is fine, but if there is no wax on the leaf, do not spray.

Bentazone controls Watergrass very well so is a useful product, but do not apply it on a warm day – a cool morning is safest.

Grasses are easily controlled in peas with products such as fluazifop, propaquizafop and quizalofop, so make the most of the opportunity to clean the field of grasses, for some successful wheat and barley crops for future years!

Finally, resist the temptation to hand weed or worse, jembe. Breaking the tendrils causes the crop to fall over and damages shallow surface roots from which the crop does not recover.

Kindest regards,

David Jones

Independent Agronomist

Think Agronomy is brought to you by Cropnuts and the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation. We share the same vision for sustainable, dryland farming across Africa, and Think Agronomy is our independent voice to promote profitable, climate-resilient farming through better management of soil health, systems-based agronomy, crop diversification, and farm mechanization.

David is an independent agronomist in Kenya and a member of the Association of Independent Crop Consultants. David gives independent advice based on scientific trials and experience. Currently works with the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation.

Order our services and get to know how to improve your soil for better yeilds.