We have no excuses. East Africa has produced world-record crops of barley in recent years and coming out of a wet season with a full profile of soil moisture, into a dry and bright finish in January and February, the potential this year is enormous on farms that have taken the long view and found crop rotations that work for them.

With a large area of barley in the ground and running, thoughts now turn to keeping the crop clean of diseases to maximise the crop’s potential. The key diseases in barley are Net Blotch, possibly Rhynchosporium in some varieties, Ramularia later on and possibly Stem Rust depending on the location.

Net Blotch is the number one cause of yield loss across most of the farms I visit and managing the disease begins with assessing the risk. Older varieties such as Quench, Cocktail and Propino are very weak and have resistance ratings of 3 out of 9 for the disease (we have actually stopped trialling Quench, Cocktail and Propino as they are now very outclassed).

Planet is only slightly better these days with a rating of 4, bettered by Laureate and Grace with ratings of 6 out of 9. Candidate varieties Malgas and Neptune – currently in National Performance Trials – are rated a 7 and 8 respectively so will really move the game on for those with a close barley rotation.

Which brings us on to the next risk factor – how long since the last barley crop on the paddock? If barley is planted after barley the previous year, even if the stubble is ploughed or burnt, reduce the variety’s resistance rating by 3 points – in other words, Quench or Propino have a 0 for resistance!

Even barley planted next to a previous season’s barley stubble can suffer from the disease spores blowing on the wind for several hundred meters, so think carefully about proximity to previous crops.

Sowing late also increases the risk as the disease spores are landing in the crop and spreading with rain splash within it, as soon as it emerges. I saw a March planted crop of Planet running at 7 t/ha (31 bags/acre) this season while a crop less than one kilometre away planted in late April will struggle to reach 4 t/ha (18 bags/acre) because of immense Net Blotch pressure. As a general rule, if you plant into moisture three weeks before the onset of rains it has the same effect as raising a variety’s resistance score by around two points.

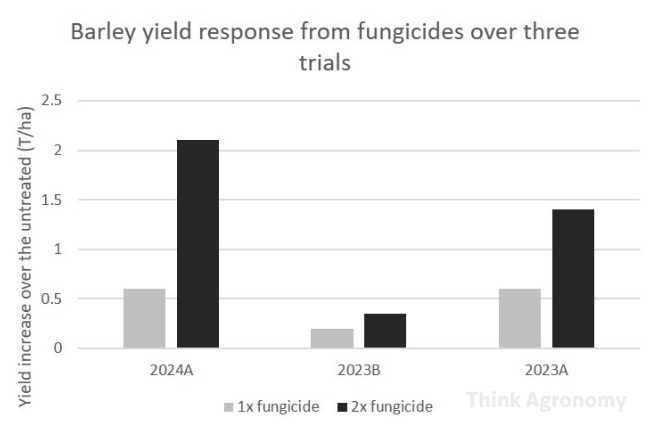

Barley needs biomass to yield. And that means tillers, leaves and stems need to be built up, from which the nutrients are reabsorbed and diverted into grain at the crop matures. This means that early tillers are important, which is why the first fungicide in barley is – relatively speaking – more important than later fungicides (this is seldom the case in wheat, where the biggest yield responses come from flag leaf sprays).

Having said that, the last three barley fungicide trials we have done show that the ‘T2’ timing just as the awns are emerging is as – if not more – important!

The key is to start early – fluopyram on the seed is very effective at reducing pressure, but you must start the spray program by the end of tillering – typically 25-30 days after the crop emerges.

The interval between the second spray (around the time that the awns emerge) should be a maximum of 28 days – remember that fungicides have minimal curative activity on diseases, so they need to be applied preventatively – that is BEFORE the disease starts hitting the leaf. In a high pressure season, keep it to 21 days between sprays.

As obvious as it sounds, chose a fungicide which has good activity on the disease that you are aiming to control – in our case Net Blotch first, Ramularia and Rhynchosporium second. For me, this means Skyway (bixafen + prothioconazole + tebuconazole), Ceriax or similar (fluxapyroxad + pyraclostrobin are the two a.i.’s we want) and Elatus Arc (benzoviniflupyr + azoxystrobin + propiconazole).

You won’t go wrong with any of the above three. They all have at least two active ingredients from different mode of action groups that have good activity on the diseases – which is important for managing fungicide resistance.

I tend to favour fluxapyroxad + pyraclostrobin early as it is very strong on Net Blotch, then either Elatus or Skyway later as the T2 spray. Skyway has the prothioconazole which is useful later on for Ramularia control – Prosaro is an option, but the bixafen in Skyway adds significantly to activity on Net Blotch and Rhynchosporium.

The withdrawal of chlorothalonil is a big loss in Ramularia protection in many countries; the sooner we get mefentrifluconazole or pydiflumetofen the better – the Ramularia work in Scotland that I see is very encouraging on these two.

Occasionally a third spray will pay, but watch the label requirements for the cut-off growth stage. You are unlikely to see a return from controlling Net Blotch at this late stage in all but the highest pressure situations, but it will control Stem Rust which will often feature in off-season barley in the Rift Valley and Laikipia.

Every season I see potato crops around Meru and Nyahururu that have lost serious yield potential from Late Blight. There are steps that can be taken to manage it however and indeed to make the most of cool and wet weather to harvest a bumper crop.

In most cases, it starts with knowing the variety. Unica needs very little input in most seasons; the problem is that fungicides have very little curative activity and are almost entirely protectant. That is to say that once a disease is in the crop, it is too late to effectively control it.

Sherekea and Shangi require minimal fungicide input too but are not quite in the same league of resistance as Unica. They will suffer from tuber blight, however, which can lead to total crop loss in store if not controlled effectively in the field.

Many European varieties, whilst having very good quality, Potato Cyst Nematode resistance often to both palida and rostochiensis and very high yield potential, are much higher maintenance varieties. Under high pressure conditions when it is raining most days and cloudy for most of the day, these need spraying at 5-7 day intervals – even then, Blight will be seen on the leaves of varieties like Markies and Taurus, and on the stems of Challenger.

Regular scouting is essential, and it is safest to remove heavily infected plants (put them in a bag and carry them out of the field – then bury them!!!)

I am finding that in the more resistant varieties, a 10-14 day spray interval is sufficient, and only in very high pressure weather conditions during rapid canopy expansion is a 7-day spray interval required on Unica and Shereka for example.

One of the most neglected factors that I try to impress on farmers is the need to get nutrition and soil structure right. These basic principles of good husbandry make an enormous difference to the ability of a crop to resist pests and diseases – dig with a spade to check for hard pans in the soil, take a soil test, leaf tissue test and above all try things out.

Applying sulphur or nitrogen to a crop is easy and often gives you a very good visual as to whether it has worked and if the plant needs it. Foliar sprays of boron, molybdenum and zinc will often give a response on our soils – multi-mix trace elements might be attractive but A) they rarely provide enough of an element if deficient and B) if and when they do improve the crop you have no idea why or what element has made the difference.

In the case of Late Blight, controlling volunteer potatoes is very important to reduce infection in neighbouring shambas and potato crops. An infected plant will produce millions of spores that are spread in the wind. Pull them out and bury them – if not for yourself, do it for the benefit of neighbouring potato growers around you.

Blackleg is a fungal disease caused by Leptosphaeria maculans, which can infect canola from emergence right through to podding and has the potential to cause severe yield loss – well over 50% if not managed properly and in the worst cases can result in total crop loss.

Spores are spread over several hundred metres on the wind from previously infected debris of any brassica crop, not just canola, and have several host weeds which can allow the disease to remain active in a paddock even with long rotations.

The fungus causes a ‘stem canker’ which restricts water and nutrient transport up the plant. It can be managed effectively by crop rotation (four or more years ideally between canola crops), fungicides and resistant varieties. Blackleg represents a very real threat and should be taken seriously in order to protect the long-term viability of canola production in Kenya.

Whilst with Sclerotinia, previous levels of infection in a block or paddock are a good infection of the likely risk, with Black Leg the disease can blow in from some distance away. So even if you have never grown canola before, the disease needs to be taken seriously. Particularly if you have neighbours growing brassica vegetables.

Blazer TT has the best resistance of any currently available variety in Kenya, but remember that this resistance is not guaranteed if you farm-save the seed to F2 generation, no matter how tempting! An early fungicide at the 4-5 leaf stage, containing tebuconazole, prothioconazole, difconazole or pyraclostrobin is a precaution to protect the crop at the early stages.

Till next time,

David Jones,

Independent Agronomist

How would you rate our article?

David is an independent agronomist in Kenya and a member of the Association of Independent Crop Consultants. David gives independent advice based on scientific trials and experience. Currently works with the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation.

Think Agronomy is brought to you by Cropnuts and the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation. We share the same vision for sustainable, dryland farming across Africa, and Think Agronomy is our independent voice to promote profitable, climate-resilient farming through better management of soil health, systems-based agronomy, crop diversification, and farm mechanization.

Order our services and get to know how to improve your soil for better yeilds.