Think Agronomy Newsletter – June 2024

Growing a big crop that looks really promising… in a season with good rainfall… until those tell-tale white bleached ears appear when you are on the home straight. There is nothing more soul-destroying than seeing a great crop become heavily infected with Fusarium. Yield alone will be damaged, but add in the quality and the bushel weight problems, and this is a problem to avoid.

So in a promising season like this where moisture is excellent and crops are full of promise, what can we do to protect the potential? The good news is that Fusarium can be managed and the risk assessed in advance so farmers can plan and prioritise crops for appropriate action with an ear fungicide.

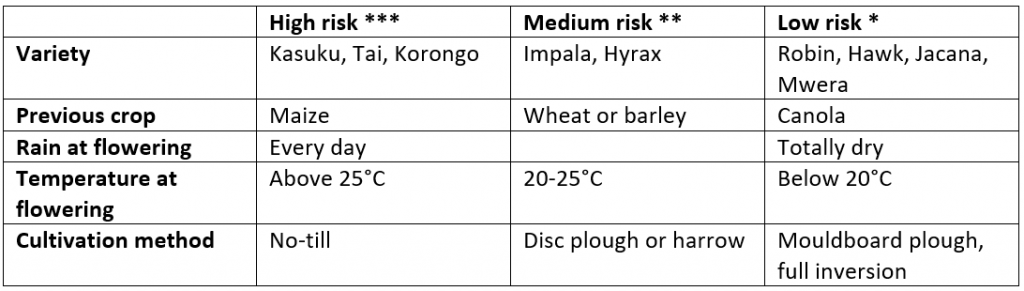

Assessing the likely risk begins with the previous crop. Fusarium survives on previous cereal crop residues and is particularly bad after maize. Wheat crops that had high levels of infection also represent a high risk to following crops. So if you grew maize or Kasuku wheat last year, you should be immediately cautious.

Weather conditions around flowering are very important, as rain and humidity drastically increases infection risk. Many farmers forget however that a dry start also actually increases risk, as there is less early breakdown of residue and the release of the conidia spores is delayed.

Variety should be a key part of any risk assessment around the ear spay. There is a lot of Kasuku grown at present which is highly susceptible to Fusarium – worse in fact than Tai. Korongo is also very weak, but Hyrax is better and Jacana and Hawk have very good resistance.

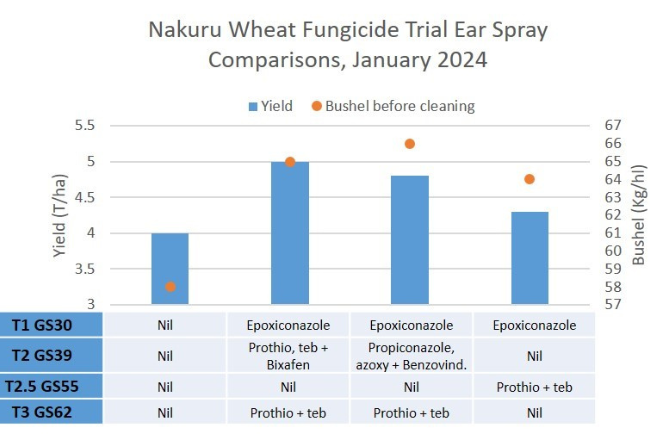

For the highest risk situation, for example, Kasuku grown after maize in a humid environment, there is only one real option for the ear spray which is a fungicide containing prothioconazole. It would also be wise to apply a flag leaf spray containing prothioconazole or tebuconazole on these crops too, as this reduces the level of Fusarium in the upper canopy in advance of the ear emerging. Important if you are delayed with the ear spray for whatever reason.

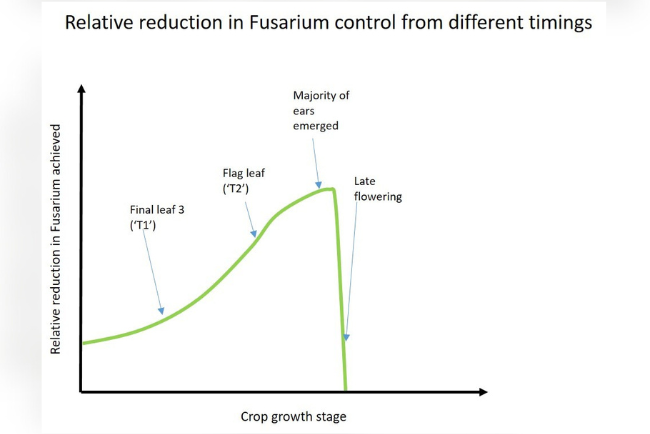

Reduction in Fusarium achieved from different timings through the crop. Once the crop reaches late flowering, it is too late and no control will be achieved.

Timing is critical – do not put yourself at risk by growing a susceptible variety on wet heavy soil. Kasuku is not a variety which achieves its best in hotter areas with Black Cotton soils anyway, and if it is too wet to spray then the consequences can be severe (for a precise application on the ear, do not rely on drones or aeroplanes. There is too much at stake).

To be effective the ear spray must be applied at early flowering, when the majority of ears have emerged and the glumes are opening. By mid-flowering the first glumes have already closed up, trapping any infection inside which the fungicide cannot reach. Ignore the old 21 day rule since the last fungicide, and go on crop growth stage instead.

For medium risk situations, a high dose of tebuconazole (>200g/ha) is often enough – for example, Hyrax in a shamba that was wheat last year. But if in doubt, money spent on prothioconazole is money well spent.

For lower-risk crops, 125g/ha of tebuconazole is sufficient. This is adequate for most crops following canola, even in hot and humid areas and it keeps the cost down considerably.

Variety resistance is one thing, but what breeders and pathologists rarely talk about is uniformity of ear emergence. Because the timing of the ear spray is so important and the window of opportunity is narrow, Fusarium is much easier to control in practice in a variety with even ear emergence. NOT Kwale which produces lots of late tillers!

What can we do in terms of cultural control to minimise chemical use? Firstly, crop rotation. Canola more than anything else reduces Fusarium significantly throughout the rotation. Secondly, chose more resistant varieties such as Jacana or Hawk in high-risk situations. Thirdly, control volunteers in the fallow. Even wheat volunteers allowed to get to flag leaf stage will build up and carry over the disease.

If you experience high levels of Fusarium regularly, you could consider adjusting planting date to coincide with drier weather conditions during flowering but this will compromise yields.

Give yourself three stars for each high-risk category, two for a medium risk and one for a low-risk box. For example, if you are growing Kasuku (high risk, 3 stars), after canola (low risk, 1 star), with some rain (medium risk, 2 stars), in a hot area (3 stars) in no-till (3 stars).

This is the time of year when we start seeing aphids arriving in canola crops. The aphids that we see on the tops of the plant are Mealy Cabbage Aphids or Brevicoryne brassicae. They multiply at the tops of the plants and if left unchecked, will cause 30% yield loss or more in a dry season. Thankfully pirimicarb controls these very effectively.

Monitor them closely (they are always worse on the headlands so walk into the crop to get a true picture), and spray when more than 5% of plants are infested. You will commonly see thresholds of 13% quoted, but these are for winter canola crops which have a greater ability to compensate and flowering in cooler weather, not the spring types that we grow.

Pirimicarb is far more selective and safer to beneficial insects such as ladybirds and hoverflies than many other alternatives, and I have never achieved anywhere like as good control from other products. Green Peach Aphids however you can safely assume to be totally resistant. So if you see small clusters of these on the tops of plants, do not spray as they are not doing a lot of damage at this stage and you won’t control them anyway.

Remember that pirimicarb needs a fine spray quality and warm conditions, above 16C. This can be challenging in cloudy weather, so keep the pressure around 3 bar and use a flat fan nozzle if conditions are marginal. Otherwise, you have the dilemma of using a low drift, air inclusion type nozzles and delaying until there is sunshine.

I hear of lots of growers using lambda-cyhalothrin, which is a big no-no in flowering canola. Even the quality formulations with bee repellents can cause a lot of damage, and if you mix a triazole fungicide with them they often mask the repellents and stop them from deterring pollinators effectively. Inevitably they won’t control the aphids either, and will kill beneficial predators such as Syrphid Fly larvae.

Northern Corn Leaf Blight (NCLB) in maize; long, cigar-shaped lesions with a dark centre.

There are a lot of reports of Northern Corn leaf Blight in Maize at the moment, across DK777, H629 and 30G19 amongst others.

If you are seeing it before tassling and you are in a high rainfall, humid area growing maize after maize last year, the disease can become quite severe by late July and August.

Azoxystrobin, tebuconazole, propiconazole and trifloxystrobin are all quite weak on NCLB. Pyraclostrobin and benzovindiflupyr are much stronger, so if you are at risk it is worth investing in a fungicide. The decision should be much easier if you are having to spray for Fall Armyworm also. And whilst drone spraying is not perfect, it is better than nothing if you are experiencing high pressure early on in the season and can actually do a reasonable job applying fungicides in maize.

Till next time,

David Jones

Independent Agronomist

How would you rate our article?

David is an independent agronomist in Kenya and a member of the Association of Independent Crop Consultants. David gives independent advice based on scientific trials and experience. Currently works with the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation.

Think Agronomy is brought to you by Cropnuts and the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation. We share the same vision for sustainable, dryland farming across Africa, and Think Agronomy is our independent voice to promote profitable, climate-resilient farming through better management of soil health, systems-based agronomy, crop diversification, and farm mechanization.

Order our services and get to know how to improve your soil for better yeilds.