Think Agronomy Newsletter – April 2024

Since its arrival in 2017, Fall Armyworm has for some been a recurring challenge. For others, much less of a problem. I have been slightly surprised this season by the higher levels of damage early on in crops than I have seen in recent years, but these are not at levels which should cause concern.

Generally I am seeing 5-10% of damaged whorls in the field from crops sown in early March which are now at the 6-8 leaf stage, but the newest three to four leaves are generally unaffected where an early insecticide has been applied. Although our attention is drawn to these older shredded leaves, they are of relatively low importance to yield – especially if they are on just a few percent of plants. What we are observing is damage from three weeks earlier which is now irrelevant.

In any case, most research on economic damage from Fall Armyworm suggests that at least 50% of whorls damage is the level at which yields start to suffer, with some studies quoting much higher levels.

Cyantraniliprole seed dressing certainly helps and gives a few weeks of protection, but it is often hard to tell after three weeks, especially where an early insecticide has been applied to control MLND vectors (imidacloprid and thiamethoxam always do more than you would think when applied at 3-4 leaf stage).

It is hard to tell if the onset of the March rain was responsible for reducing a lot of the pressure, or earlier insecticides. Indoxacarb or emamectin applied at 5-7 leaf stage have undoubtedly killed a lot of larvae, which are dead and visible on the outer leaves now, but weather conditions since the rains began are far less suitable for the adult moths.

Remember that the likes of lufenuron, teflubenzuron, and flubendiamide only really offers control of 1-2 instage larvae. Abamectin, chlorantraniliprole, emamectin benzoate, indoxacarb and pyriproxifen are all much stronger on larger stages of instar, but not to be complacent.

We can isolate the differences with experiments in pots or test tubes to looks at mortality of the larvae, and in fact how residual the products are on the leaf by introducing larvae to treated leaves after an increasing length of time (I’m not convinced that control of large larvae in the whorl from direct spray contact is important; these guys are well hidden and much tougher than smaller larvae that pickup chemical from the leaf surface).

The reality of Fall Armyworm control is that we don’t actually succeed in killing many of the larger larvae; the more profound outcome from the application of insecticides is killing much smaller larvae as they hatch; much more susceptible to the chemical.

Interestingly I find it very difficult to validate the effect of products with ovicidal activity such as novaluron. Whilst quite ambitious claims are made by manufacturers I have yet been able to isolate this from hatched larvae dying at 1st instar from feeding on a treated leaf.

In terms of actions going forward, if you are seeing damage on 50% of whorls, and it is active (i.e. on the current emerging leaves) – spray a suitable insecticide. In the longer term, the following steps are important:

Epoxiconazole offers probably the best control of Yellow Rust available. It does enough at T1 to keep Stem Rust from appearing later (I have lost count of how many trials we have done where we leave off the T1 and do not apply any fungicide until flag leaf. It looks clean then, but by the end of flowering the differences are huge).

Tebuconazole is a strong option; virtually no activity on Septoria and weaker on Yellow Rust. My main concern is that we are almost too reliant on tebuconazole later in the program.

Various mixes of propiconazole + cyproconazole are available and very useful. Whilst they are limited in Septoria activity, it is a useful way of diversifying away from tebuconazole, and not using a strobilurin so early in the program (FRAC guidelines limit us to two per crop).

Azoxystrobin mixed with cyproconazole or tebuconazole is strong on Stem Rust and Yellow Rust. But raises the question as to using one of the two mandatory strobilurins this early.

Prothioconazole + tebuconazole adds useful Septoria activity, at a price. But leaves us very reliant still on tebuconazole (prothio adds very little on Rusts).

More expensive co-forms with SDHI’s such as Ceriax, Skyway and Elatus Arc are all good but unnecessary at T1 with our low Septoria pressure (having said this we are investigating their place at T1, followed by a ‘hybrid T2.5’ – a spray combining the flag leaf and early ear emergence. This is much more plausible on more varieties with robust disease profiles such as Mwera, Impala and AGV249.

As always, base the T1 decision on your variety and the specific disease concerns in your location. In Nakuru or Eldoret Yellow Rust is less of a problem, particularly if you are growing Hyrax or Impala, so tebuconazole, propiconazole, cyproconazole etc would be fine. But on the Mau or in Timau, if you are growing Kasuku which is weaker on Yellow Rust you probably want epoxiconazole.

Maize – fallow – Maize – fallow – Maize…

Or cereal-fallow in Narok or Timau perhaps. Our soils are capable of so much more and deserve so much better that this cycle which has resulted in crop yields declining or remaining static at best over the past few decades.

We can talk at length about why we need diverse crop rotations to manage pests and diseases, but what if we could get to a place where we no longer even need the fallow phase?

In the past, the fallow phase existed because there were very few suitable alternative crops, and because farmers saw a steep decline in yields where they tried to plant again immediately after harvest.

Our knowledge of double cropping has come a long way in the past few years. After a decade of notill, crop rotation and attention to soil structure these farms are capable of storing much more moisture and cycling nutrients so that they are available to the plant.

Moisture almost certainly can be limiting, especially when a very deep rooting crop such as sunflowers or sorghum have used a lot of deep moisture, but I believe that we have also overlooked Nitrogen. I increasingly find in trials where we plant a cereal straight after canola, that timing of Nitrogen is crucial and can make the difference of a 3 t/ha crop to a 6 t/ha crop.

The clues are there – where I look through the thousands of data points on Deep Nitrogen that we have collected over the years, typically there is 100-125kg/ha residual Nitrogen straight after harvesting well-nodulated peas. After a 6 month fallow of mineralisation of organic matter we typically see 180-250kg/ha of N. Nitrogen form mineralisation has been hugely underestimated here.

Another dimension here is that timing of planting is crucial. When farms experiment with double cropping individual fields they tend to do well, as they are prioritised with less time pressure. Inevitably, after a dry harvest these crops establish later and are often dry planted. This delay causes a knock on late harvest and the cycle of harvesting crops which rain out of rain too early, then are harvested in the wet.

On farms that regularly double crop, I am increasingly applying a greater proportion of the Nitrogen in the seedbed by using blends containing more N such as 23.23.0. It is important to be careful about how and where this is placed however; next to the seed, in wide rows can cause a lot of damage, especially in crops such as canola.

The good news is that farms which were seeing 40% lower yields from double-cropped wheat or barley seven years ago are now much closer to 10% below. The next challenge is to find a rotation which allows grass weeds to be controlled; after years of planting wheat every October, planting an off-season broadleaf in March just allows the Brome to lay dormant during the fallow for the next cereal crop in the usual pattern.

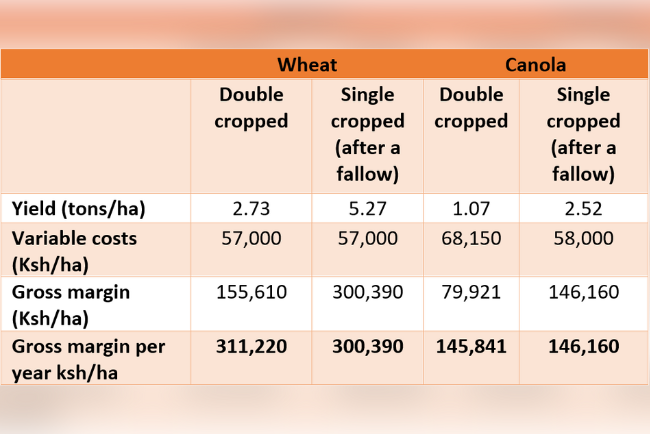

The financial results from one farm that has a rotation of wheat – canola – barley – peas makes an interesting comparison. After single cropping – i.e. four crops in four years – the wheat yields dropped to 2.73 t/ha from a long-term average of 5.27 t/ha when they were growing just one crop a year. The actual cost of growing the crop was identical, so there was a slight improvement in the total margin from 300,390 ksh/ha per year to 311,220 ksh/ha per year.

The situation with canola was similar, with some terrible stressed crops and much higher insect pressure which is reflected in the variable costs. The lesson is tread carefully, and follow some important points:

Till next time,

David Jones,

Independent Agronomist

How would you rate our article?

David is an independent agronomist in Kenya and a member of the Association of Independent Crop Consultants. David gives independent advice based on scientific trials and experience. Currently works with the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation.

Think Agronomy is brought to you by Cropnuts and the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation. We share the same vision for sustainable, dryland farming across Africa, and Think Agronomy is our independent voice to promote profitable, climate-resilient farming through better management of soil health, systems-based agronomy, crop diversification, and farm mechanization.

Order our services and get to know how to improve your soil for better yeilds.