Legumes for a crucial part of the crop rotation on many levels, adding valuable soil nitrogen, reducing root diseases such as Take-all and Fusarium in cereals, improving soil structure and allowing control of grass weeds such as Brome and Ryegrass.

Something that I have seen first-hand over the last few years in Kenya is the effect that legumes have on improving phosphorus availability – I visit several farms where soil test P levels were around 5ppm of Phosphorus 10 years ago when they were mono-cropping maize or wheat and are now over 20ppm. This immediately translates into improved crops and big savings in cash and risk for the farmer.

Many legumes also reduce levels of damaging nematode species such as Root Lesion species. No wonder the best crops I look at have legumes in the rotation. It is hard to put a finger precisely on the benefit, but I can tell you that I have never visited a farm consistently achieving over 25 bags per acre without a rotation; 40 bags is reliable once some diversity is introduced in the form of pulses, sunflowers and canola.

Harvesting Peas

In reality, when viewed in isolation legumes will not make the money that wheat or maize does. But then defenders in football rarely score goals; yet they are essential to win matches and ultimately trophies. So what are the pulse options, and how best to go about identifying a suitable crop to try out for 2023?

Peas – one of the least consistent of all crops, combining peas requires a well-structured, level seedbed and a relatively dry start to avoid lush growth and to get ahead of Ascochyta. Being a large seed, they lend themselves to planting deep into stored moisture, allowing them to get a head start on disease and earlier harvest.

Typically costing around 55,000 Ksh/ha (428 USD/ha) in variable costs (seed, sprays and fertiliser), a large amount of this is upfront seed cost. Yields range from 1 t/ha when planted poorly in a dry or extremely wet season, to 4 t/ha in good conditions with small amounts of frequent rainfall. Peas are very susceptible to Ascochyta in very wet seasons but do not be sucked into the hype around spraying multiple fungicides as these are rarely effective and on occasion do more damage to the crop. Aphids and Bollworm need watching closely so sprayer capacity is a must.

Chickpeas – a true dry season crop that thrives on stored moisture – not for cool environments when temperatures get into the single figures or where in crop rain is likely to be over 250mm. Many a great looking crop has disappointed at harvest having been full of Botrytis Grey Mould. Kabuli’s tend to be the easiest crop to market and sell, and need planting at depth to ensure strong plants – great for moisture seeking if you are prepared to plant slowly. There is zero tolerance of Bollworm damage, so they need to be monitored closely.

Dry beans do well in most areas of Kenya, although I tend to see most disappointments come from choosing the wrong variety at higher altitudes and planting in high rainfall seasons. More of an off-season, opportunistic crop dry beans would appear to need a high level of phosphate fertiliser in the seedbed and consistently benefit from topdressing (something that is clear in other parts of the world too). Being very uncompetitive against weeds and requiring a large amount of labour to weed and hand harvest, when costed up properly I rarely see a dry bean crop that makes money.

Faba beans are arguably the most wet-weather tolerant of all crops except rice, thriving in high rainfall and wet soils. They are very slow developing and can take 6 months to harvest typically. Ensure that the planter is well calibrated to evenly distribute the seed – weeds have a long time to exploit any gaps in the crop. Generally fairly cheap to grow at 25-30,000 ksh/ha, faba beans have a very limited export/premium market so the aim is generally to a high starch / moderate (around 28%) protein product for livestock feed compounds.

A fascinating and relatively new crop is Lupins. Tolerating both moderately wet and very dry conditions. Lupins benefit from being inoculated with rhizobium more than any other legume; it is very distinct in the field when the inoculant is applied at sowing. The rhizobium strain for lupins is also the most acid tolerant, handy for the vast majority of Kenya’s soils!

Typically costing 30,000 Ksh/ha (USD 234/ha) in variable costs, White Lupins are relatively unique in that they are Mycorrhizal and Proteoid, allowing them to access a large amount of P from the soil; large savings in the short term at least can be had from not requiring seedbed fertiliser.

Check the germination of seed before planting however as lupins are notorious for germination problems if not handled gently.

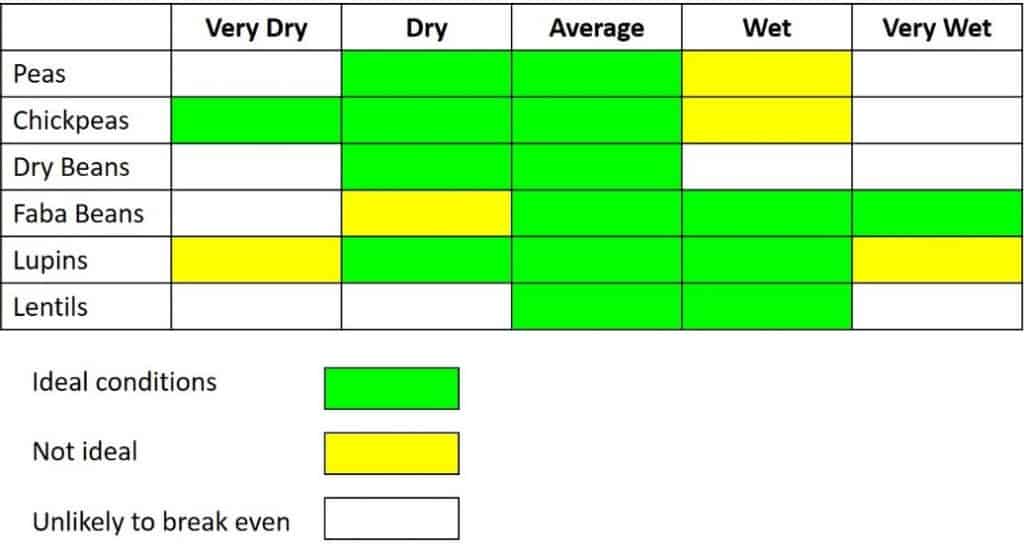

Suitability of pulses to rainfall level; green represents the optimum relative rainfall, yellow is sub-optimal but manageable, and white is where the crop will most likely perform poorly and not break even.

You have prepared the soil, got the planter serviced and the conditions are just right. You have the new certified seed of your favourite variety or perhaps a new superstar variety. Now to calibrate the planter… but at what seed rate?!!

Ultimately most crops have an ideal range of plant population, for the environment in which they are being grown, within which they will achieve their optimum yield. Identifying this range is the first step, after which the farm has to set the seed rate having adjusted for establishment losses in the seedbed.

Seed rate and variety trials give us a fairly good indication of optimal planting rates

As a general rule, too high a plant population for wheat and there is a risk of lodging or the crop running out of moisture before the grain has properly formed, leading to poor grain quality and reduced yield; too low and yield potential is lost.

Higher seed rates are also one of a number of measures that can reduce weed competition, helping reduce head numbers of Ryegrass and Brome and subsequent seed return.

In drier environments, such as Kenya’s lower Narok or Laikipia, 150-175 seeds per m2 is about right for most varieties, so that they tiller – and have the ability to shed tillers – if it becomes too dry later on. On deeper soils and with good stored moisture, up to 200 seeds/m2 is realistic. In wetter environments in the Rift Valley, where the crop is unlikely to run out of moisture in the main season and grows relatively quickly, 225 seeds/m2 or even higher is about right. We have seen in trials that dropping the seed rates from 200 to around 130 seeds/m2 loosing around 10% yield in Nakuru, and inviting more weeds into the crop.

For high fertility situations in Timau and Mau Narok, where the high altitude allows crops to grow slowly and tiller strongly, it is also sensible to reduce seed rates to avoid lodging. I would never plant Njoro 2 or Kwale above 175 seeds/m for example, although varieties such as Kasuku with far stiffer straw can be planted at 225 seeds/m.

Some wheat varieties appear to be particularly sensitive to low seed rates because they produce very few tillers; Kasuku and Robin are two such varieties. Interestingly, Mwera however appears to be able to compensate for low populations by producing long ears with increased number of grain sites. Kwale and Hawk produce far more tillers so do not require such high seed rates.

It is important to remember that seed rate is measured in two ways, seeds per m2 or hectare, and weight per hectare – and to convert seeds per m2 to kilograms per hectare, you need to know the Thousand Grain Weight.

Thousand Grain Weight (TGW) can vary considerably; at 43g, you need to plant 86kg/ha to achieve 200 seeds/m2. At 55g, you need to plant 110kg/ha. Ignore TGW and you are planting blind. If the seedbed is poor and establishment likely to be reduced, always increase the seed rate.

Suggested seed rates:

| Low fertility / hot areas below 2,000m | Good rainfall, below 2,100m | High altitude above 2,300m and fertile | |

| Robin, Kingbird, Mwera | 175 – 200 seeds | 250 seeds | 225 seeds |

| Kasuku, Hyrax | 175 – 200 seeds | 250 seeds | 250 seeds |

| Kwale, Njoro 2, Korongo, Hawk | 150 – 175 seeds | 200 seeds | 150 seeds |

Seed rates in seeds/m2 (assuming a good 90% establishment)

Sulphur has got a lot of attention over recent years, and perhaps rightly so. We all know the story; factories are cleaner, so less sulphur from industrial processes are emitted into the atmosphere and as a result our crops have less Sulphur than they did perhaps 20 years ago.

But is this accurate in Kenya, or is it a convenient story used by the fertiliser industry to sell us more complex and expensive products?

There is no doubt an element of truth in this; crops do need reasonably large amounts of Sulphur, but when I look back at over 10 seasons worth of data from strip trials on farm and small plot work, it is far from overwhelming. In fact at one point we had completed 34 trials with sulphur and had not seen a significant response in any of them!

There are results where 15-20kg/ha of S has improved yields by perhaps 5%, but these are occasional and always barely significant.

Why is this? There are probably a number of factors involved, from sulphur being released in organic matter, a level of atmospheric deposition still occurring, geothermal venting (think Naivasha!) and weathering of rocks. Whatever it is, we simply do not see yield increases regularly in trials – and if they do they are very small.

Other ways to check out sulphur nutrition are to soil test; not a great guide as it is readily leached in heavy rain (but 4-5% organic matter soils will always be releasing some S), leaf testing helps but is quite transient (Sulphur content will change rapidly) and visually looking for symptoms of yellow newer leaves.

I have been Grain Nutrient testing for a number of seasons now across many farms in Kenya and this is a good indicator of sulphur supply; 0.12% S is considered a reliable threshold above which the crop is well supplied and I am yet to see a sample of wheat or barley below this, even on crops which have not received ANY sulphur fertiliser.

There is certainly no harm in applying small maintenance doses, and in fact this is fairly convenient on soils which respond well to Magnesium, by applying some magnesium sulphate at planting. Or a Urea-Sulphur blend like a 40+6S at topdressing.

A word of caution and perspective. A lot of our trials our carried out on soils where structure is good, a crop rotation is in place and crops are able to root deeply. As Sulphur is highly mobile in the soil we should not ignore the fact that it can be quickly washed below the depth of rooting – very possible in continuous maize on years of disc ploughing.

If you want to see if you can save money on sulphur, do it sensibly; start leaving untreated tramlines before you drop it out of your fertiliser programs altogether.

Till next time,

David Jones

Independent Agronomist

Think Agronomy is brought to you by Cropnuts and the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation. We share the same vision for sustainable, dryland farming across Africa, and Think Agronomy is our independent voice to promote profitable, climate-resilient farming through better management of soil health, systems-based agronomy, crop diversification, and farm mechanization.

How would you rate this article? Click link

David is an independent agronomist in Kenya and a member of the Association of Independent Crop Consultants. David gives independent advice based on scientific trials and experience. Currently works with the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation. Follow him on Twitter @Kenya_agron

Order our services and get to know how to improve your soil for better yeilds.