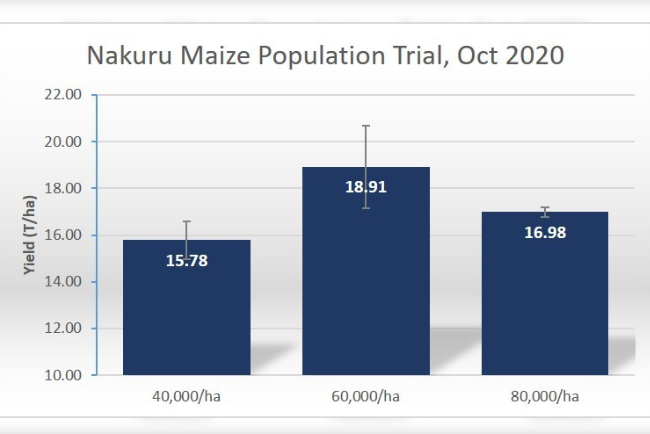

For five years we have tested maize plant populations, and every year we find that the existing advice to plant at 45-50,000 plants/ha does not produce the highest yields or the highest margin – or the best weed control.

It is very clear that maize plant populations across the country need a fundamental re-think, and this goes back to getting several basic steps right. We test maize plant populations within our trials every season – sometimes across all varieties at 45,000/ha vs 80-90,000/ha to see how individual varieties respond and cope – and sometimes focused on an individual variety looking at several different seed rates to see where the optimum might be.

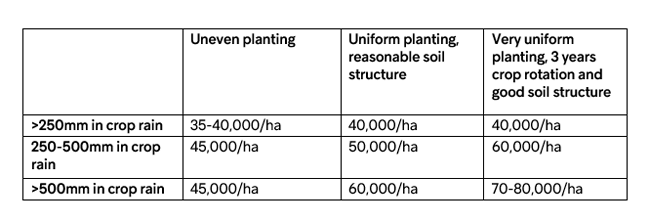

To be absolutely clear, when we are talking about maize populations, we are talking about UNIFORMLY PLANTED populations. All of this goes out of the window if plants are not evenly spaced, if seed and plants are not uniform (most ‘hybrid’ seed we test is not in fact sufficiently uniform to qualify as a distinct variety), and if planting depth is uneven and plants are emerging more than 12hrs apart.

Getting each plant out of the ground at the same time is crucial to avoid later emerging individuals effectively becoming weeds. This is why when you look at Youtube videos of maize being planted in Brazil, the USA, or Germany, the farmers make every effort to ensure the seed bed is level (no planter bounce!) and the planter is driven slowly at 6-8kph max.

What factors affect optimum population?

In drier areas, lower populations will always give more stable yields. Thinner soils with less moisture-holding capacity will also tend to have a lower optimum population. We found after three off-seasons in Nakuru (Kenya) planting in August, that there was in fact no benefit from increasing the population above 45,000/ha. In the traditional main season of March planting however, we have never seen 45,000 plants outperform 80-90,000/ha.

Crops with limited rooting ability (continuous maize with diseased and nematode-damaged roots, compaction from disc ploughing, etc) will clearly have a much lesser ability to find water in the dry period. They will be affected by stress far more quickly than a crop in a chisel ploughed soil with years of crop rotation. This is probably the number one reason why Kenyan farmers have not increased their populations as farmers in the rest of the world have. And why our yields have declined for years.

Even if the foundations of good soil structure, rotation, and good planting are in place, not all varieties are suitable for higher populations. H6213, EAS 600-15A and 30G19 often fall down in trials as not having sufficient standing ability or early uniformity. These varieties have their merits; just do not plant them above 50,000/ha.

DK777 on the other hand is very uniform, sufficiently short, and sturdy to cope with high populations. Contrary to popular social media belief, DK777 – as good as this variety is – does not cope well with drought. Later planting and drier June-July periods always see that variety fall down the yield charts. The data does not lie.

You have grown a successful crop, nurtured it for six months, and got all the details right. The last hurdle is now getting it into the store. Not all farmers have access to brand-new combine harvesters; most rely on older machines run by contractors. Here are some simple checks and questions to ask the person entrusted with harvesting your precious crop:

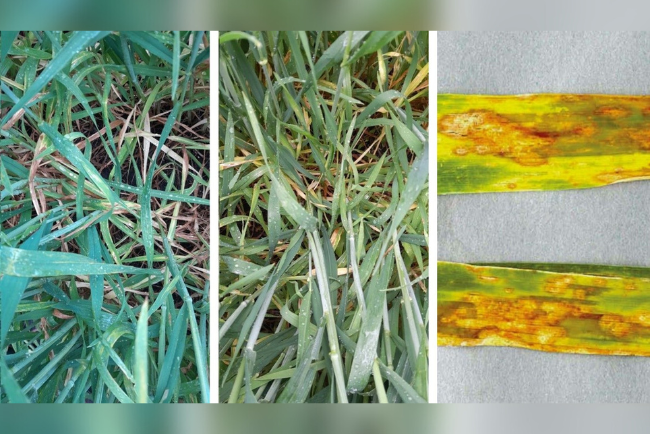

Having had to look so hard for Stem Rust this season, I almost missed the fact that the good rains have brought about a lot of Septoria. Not the more recognisable Septoria tritici, but Septoria nodorum.

Septoria tritici can be identified as tan lesions filled with small black dots or pycnidia. These are not visible to the naked eye in nodorum and the lesions usually have a more ‘watery soaked’ appearance, which is often dismissed as older, naturally senescing leaves.

Our site in Nakuru (Kenya) this season is after wheat, so there is plenty of inoculum on the stubble from last year’s crop which has added to the infection levels.

Septoria nodorum is a peculiar disease in that it damages crops in many forms; seedling death, leaf, and green area loss, and also ear infection that results in small, shrivelled grains.

Seed treatment helps reduce seedbed losses, and foliar fungicides the latter two. There is not a great deal of information on fungicide activity for nodorum, other than strobilurins (e.g. azoxystrobin, pyraclostrobin) and some triazoles (tebuconazole, cyproconazole and propiconazole) are not effective. SDHI’s such as bixafen, the triazoles prothioconazole and epoxiconazole, and chlorothalonil are all relatively effective and give good reductions in the disease.

Last year we noticed that the Hyrax had quite notable amounts of nodorum on the ear (also known as ‘Glume Botch’), so watch this variety closely.

The main lesson is to take this disease seriously and not to misdiagnose it as nitrogen deficiency or old, senescing leaves. In high rainfall areas, especially where wheat is following wheat, use the right fungicide and use it early at Growth Stage 29-31.

Key facts – Septoria nodorum

Till next time,

David Jones

Independent Agronomist

How would you rate our article?

Think Agronomy is brought to you by Cropnuts and the Centre of Excellence for Crop Rotation. We share the same vision for sustainable, dryland farming across Africa, and Think Agronomy is our independent voice to promote profitable, climate-resilient farming through better management of soil health, systems-based agronomy, crop diversification, and farm mechanization.

Order our services and get to know how to improve your soil for better yeilds.